Conservative Conference 2024: The uphill battle to unite Tory voters

James Crouch analyses the party's perceived disunity and how well placed the leadership contenders are to respond to it

Despite a bad start for the new government, the Conservatives need to go to their conference this year thinking seriously about the many problems they face as a party. Opinium has tracked the party’s brand and reputation over the last few years, from the heights of the Hartlepool by-election win to the depths of a Tory parliamentary party without a single representative from Oxfordshire.

The Conservatives need to think carefully about the leader they choose and whether they are likely to respond to the wide-ranging challenges the party faces. The particular challenge I want to highlight from our latest polling with The Observer on the eve of the Conservative Party conference is one of disunity—both within the party and within its voter base.

In 2021, the Conservative Party was seen as relatively united, in fact it was one of its strongest scores. The summer of 2021 was a particular high point where the party had a net score of -4% on “being united”, according to voters (not a bad score for a political party!). Since then, the party has dropped 31 points on this, from -4% at one point in 2021 to -35% in the lead-up to this conference season. During the general election campaign it was even worse.

But the party also has to try and bring together very different, divergent interests. Voters that left the Tories for Labour and the Liberal Democrats want a better offering on public services, the NHS, and the cost of living, while voters that left for Reform want a better offering on immigration. Truth be told, the party can’t really move forward by only appealing to one or the other. The next leader needs to appeal to all parts of the Tory electoral coalition to be a truly national party and win a general election.

The "acceptability" of the different leadership contenders

To this end, we asked 2019 Conservative voters what they thought of the four Conservative leadership candidates in terms of their “acceptability”. In a nutshell, how acceptable or unacceptable would each of the candidates be to the people the party needs to win over if they became leader? Why have we done this, you might ask.

Firstly, asking for leadership preferences at this stage, even amongst Conservative voters, past and present, gives pretty unclear results. Voters, unlike members, just have not engaged with the race that closely up until now.

Secondly, leaders make their impact in office, and quite rightly, many will have an open mind at this stage. What we are interested in is who has made an impression in the minds of past and present Conservative voters, and how much of this is already negative before they have even taken office. When the task is to bring unity, having a large minority unhappy with you is probably a bigger problem than the number who actively support you at this stage.

The contenders

The headline results are simple: all candidates have a net positive score on acceptability, although some candidates have better scores than others. Amongst 2019 Conservative voters:

Robert Jenrick has a net acceptability score of +19 (36% acceptable vs 17% unacceptable as leader)

Tom Tugendhat has a net acceptability score of +15 (35% acceptable vs 20% unacceptable as leader)

James Cleverly has a net acceptability score of +14 (38% acceptable vs 24% unacceptable as leader)

Kemi Badenoch has a net acceptability score of +5 (32% acceptable vs 27% unacceptable as leader)

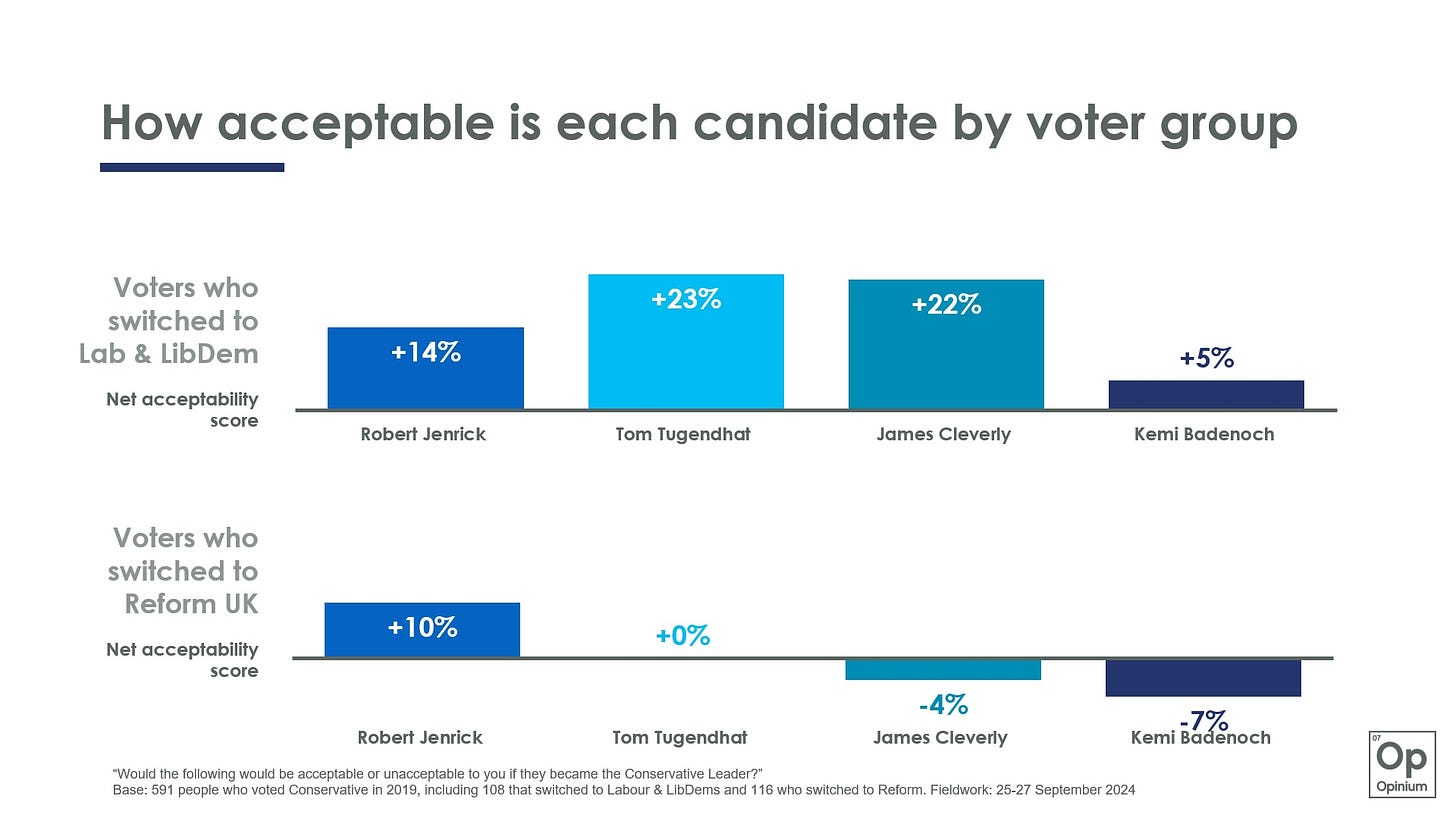

In summary, while the various contenders have relatively similar levels of acceptability, some will be surprised by the narrower score for Kemi Badenoch. Why this is the case can be seen when we look at the views of former Conservative voters based on who they left the party for. Let us, for a moment, crudely describe those who left the Conservative Party for Labour and the Lib Dems as a proxy for the views of the “centrist wing” of the party, and those who left for Reform as a proxy for the views of the “right wing” of the party.

The centrist wing of the party gives two candidates a pretty strong score. Amongst these former Tory voters who left for Labour and the Lib Dems, Cleverly has a net score of +22 (41% acceptable vs 19% unacceptable), while Tugendhat has a net score of +23 (36% acceptable vs 13% unacceptable). Jenrick won’t be unhappy with a net score of +14 (31% acceptable vs 17% unacceptable), but Badenoch comes lowest with a net score of +5 (31% acceptable vs 26% unacceptable).

The right wing of the party gives us a different picture. First, there is only really one candidate with an actively positive score amongst those who left the Conservatives for Reform UK: Robert Jenrick, with a net score of +10 (34% acceptable vs 24% unacceptable). However, two candidates have negative scores: James Cleverly on -4 (29% acceptable vs 33% unacceptable) and Kemi Badenoch on -7 (28% acceptable vs 35% unacceptable). Perhaps the most noticeable takeaway is this wing of the party’s voters shows much less enthusiasm for all of the candidates than those voters lost to Labour.

A somewhat surprising element here is Kemi Badenoch. She is often described as a candidate of the right, but having over a third of switchers to Reform think of her as unacceptable as leader seems a particular challenge. By comparison, for the candidates from the centrist wing, Tom Tugendhat benefits from having edged a slightly better net score (+0) amongst this group than James Cleverly.

All this combined suggests that Jenrick and Tugendhat have the edge as candidates who could unite all wings of the party, while Badenoch will struggle if part of her appeal is to supposedly win back Reform voters.

All of this being said, the party conference could entirely change this dynamic, both with voters, members, and MPs. We can only really poll this confidently once the final two candidates make a clearer impact with the wider electorate, but this is the state of play going into the party conferences.