Are we heading for a coalition (of chaos)?

Adam Drummond, Head of Political and Social Research, on whether the Tories can rely on the C-word again

Since the local elections, Labour have argued that they are on course for a majority in the next general election while Conservative commentators have seized on Labour having a smaller lead in the National Equivalent Vote (an academic estimate of what the national vote share would have been if every part of the UK had had local elections on that day) than in they have in general election polling to claim that the next election is very much up for grabs.

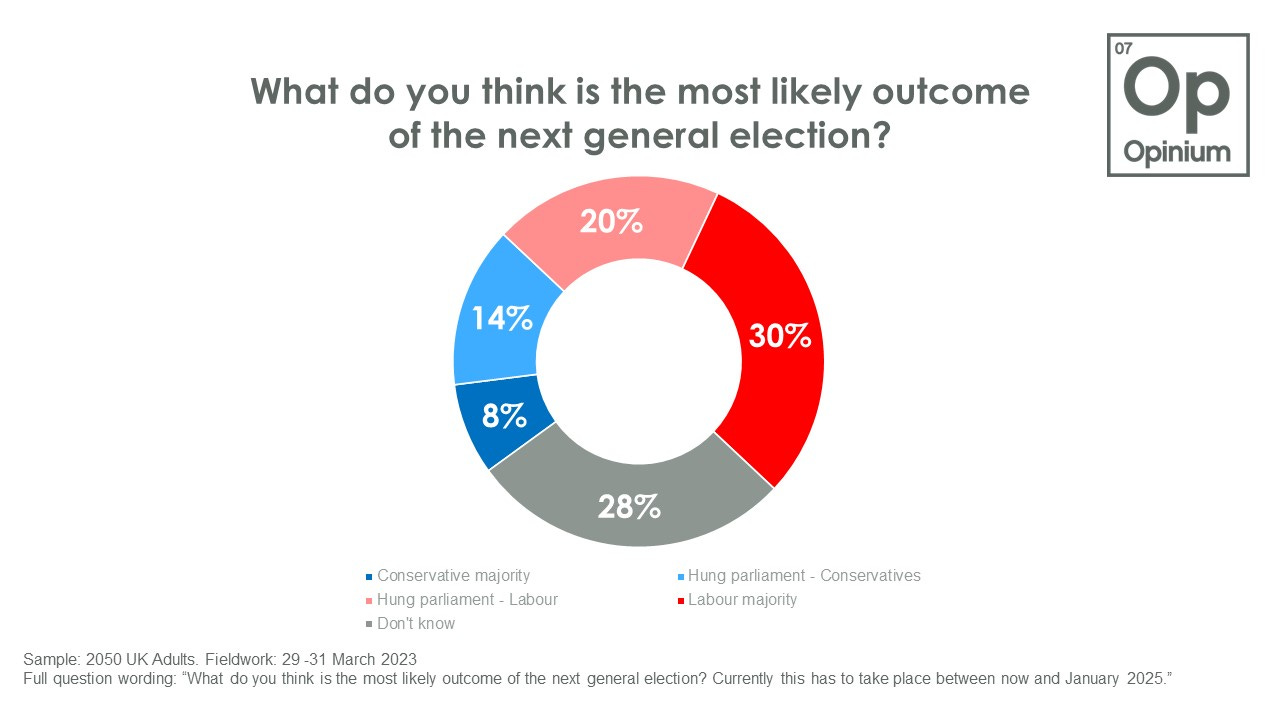

There are a number of reasons to doubt both claims although more the latter than the former and “Labour majority” vs. “Labour being the largest party in a hung parliament” both point to Rishi Sunak moving out of Downing Street. But talk of a hung parliament has inevitably led to comparisons with the 2015 general election which holds a special place in Tory hearts. Could the revival of the “coalition of chaos” conversation be used to similar effect in 2024?

There are two problems with the idea of a re-run of the “Ed Miliband in Alex Salmond’s pocket” posters:

The first is that, unlike in 2015, polls consistently show Labour with a commanding lead and Keir Starmer ahead of Rishi Sunak on various leadership metrics. Therefore the choice between hung parliament and majority government is not between Conservative majority and Labour minority but, much more likely, between Labour majority and Labour minority. Therefore if you are arguing for voters to reject a hung parliament above all other considerations, their best bet for doing so (assuming the Conservatives do not stage an era-defining turnaround) is to vote Labour.

The second is that the various alternatives to a “coalition of chaos” aren’t seen by voters as nearly as stable as the Conservatives would like.

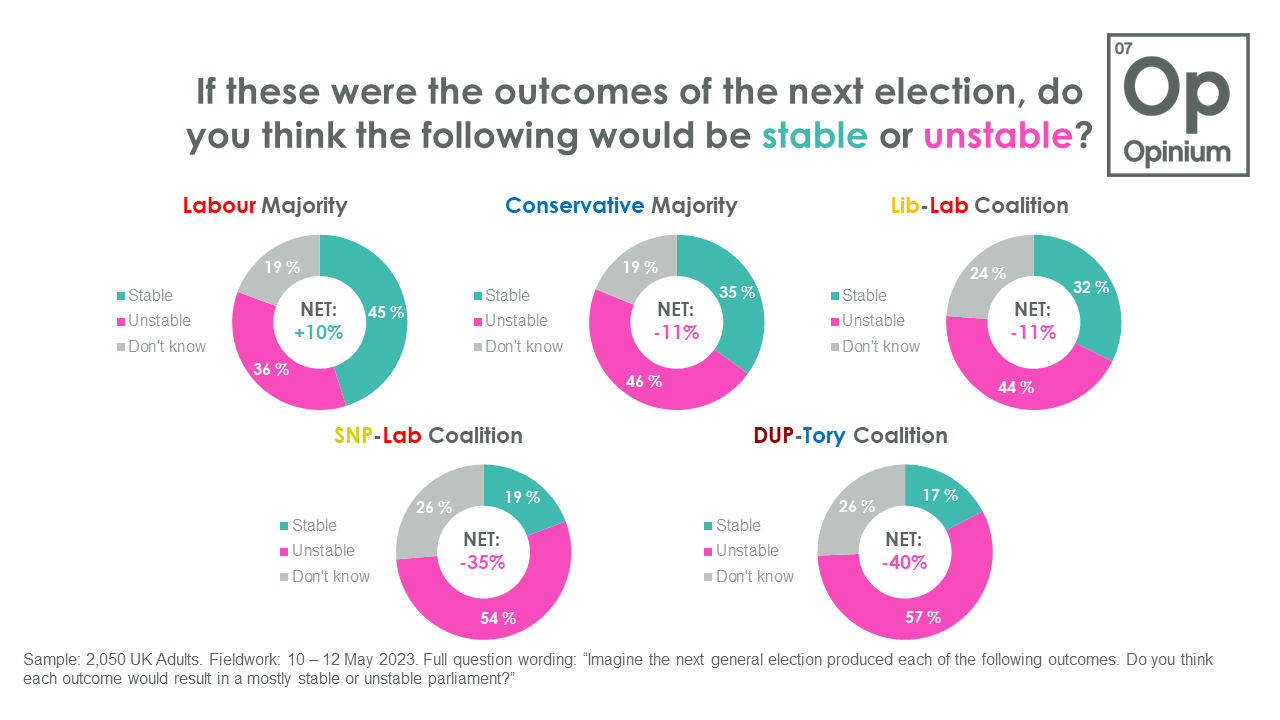

In last week’s poll we asked voters whether they thought various possible outcomes of the next general election would be stable or unstable.

The only option with more people expecting stability than instability was a Labour majority. A Conservative majority was seen, on net, as being just as stable or unstable as a Labour-Lib Dem coalition. Given the relative stability of the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition government vs. the years of Conservative government since then, this is perhaps unsurprising. What is also interesting though is how different views of a coalition containing the Lib Dems are vs. coalitions that do not contain them.

A Labour-SNP coalition is seen as very unlikely to be stable but the problem for the Conservatives in pressing this argument is that a) this is a less likely outcome of the next election than either a Labour majority or a Labour-Lib Dem deal (due to both the SNP’s problems in Scotland and Labour’s much improved polling position now vs. before the 2015 election) and b) the option seen as least stable is a Conservative-DUP coalition, something that the Conservatives effectively proved from 2017-2019.

For Conservatives, a lack of faith can also be found in worrying places. A quarter (24%) of 2019 Conservative voters think a Conservative majority would be unstable, while 38% of Leave voters think the same thing. Overall, if the Conservatives are launching a stability-based attack, their defences are looking frail.

Similarly, even a fifth (19%) of those currently intending on voting Conservative say that a Labour majority would make for a stable government. It is possible therefore that prioritising the majority vs. hung parliament angle may push wavering Lab/Con switchers towards Keir Starmer as the more stable option. This highlights once again the central problem Rishi Sunak has which is that while his own ratings are competitive with Keir Starmer (albeit generally a few points behind), the party he leads is deeply unpopular and distrusted.

But stability comes in different forms. One indication of base stability is party unity and this may give an indication as to why the numbers for a Conservative majority are so low. A couple of weeks ago, we asked if the public thought the Conservative party is united. Only 17% thought they were, a majority (54%) thought they were not. The net score of -37% is a stark contrast to the Labour party’s figures for the same metric. 31% agreed that the Labour party is united vs. 37% who disagreed. The net figure is a relatively healthy -6%.

At the moment the public believe Labour will win the next general election and this is likely feeding into some of their perceptions about stability:

2019 Conservatives were a little more hopeful for the party, with 35% expecting the Conservatives to be the largest party. However, a plurality of them still see a Labour win in the future, as two fifths (40%) expect Labour to be the largest party.

The key caveat with all of this is that much is dependent on the state of the parties remaining much as it is at the moment. Local elections are of limited use in predicting general elections but their main function is to tell us whether or not we can trust general election polls of voting intention. The results were broadly consistent with the story polls tell us at the moment but it’s never wise to assume nothing will change. However, while talk of a hung parliament may be necessary by Conservative strategists to buck up morale and discipline, every other bit of data we have tells us that asking voters to prioritise stability over chaos is likely to benefit Keir Starmer.

As seen originally in Lansons-Opinium Political Capital.

Correction: an earlier version of this post mislabeled the “Lib-Lab coalition” and “Conservative majority” charts. This, and the text, have been amended